The Syntax Layer

Nov 29, 2025

"The question is: will non-programmers develop an intuition at a different level of abstraction that lets them guide AI as well as—or better than—traditional engineers? I see both sides on my timeline." - Cameron Franz

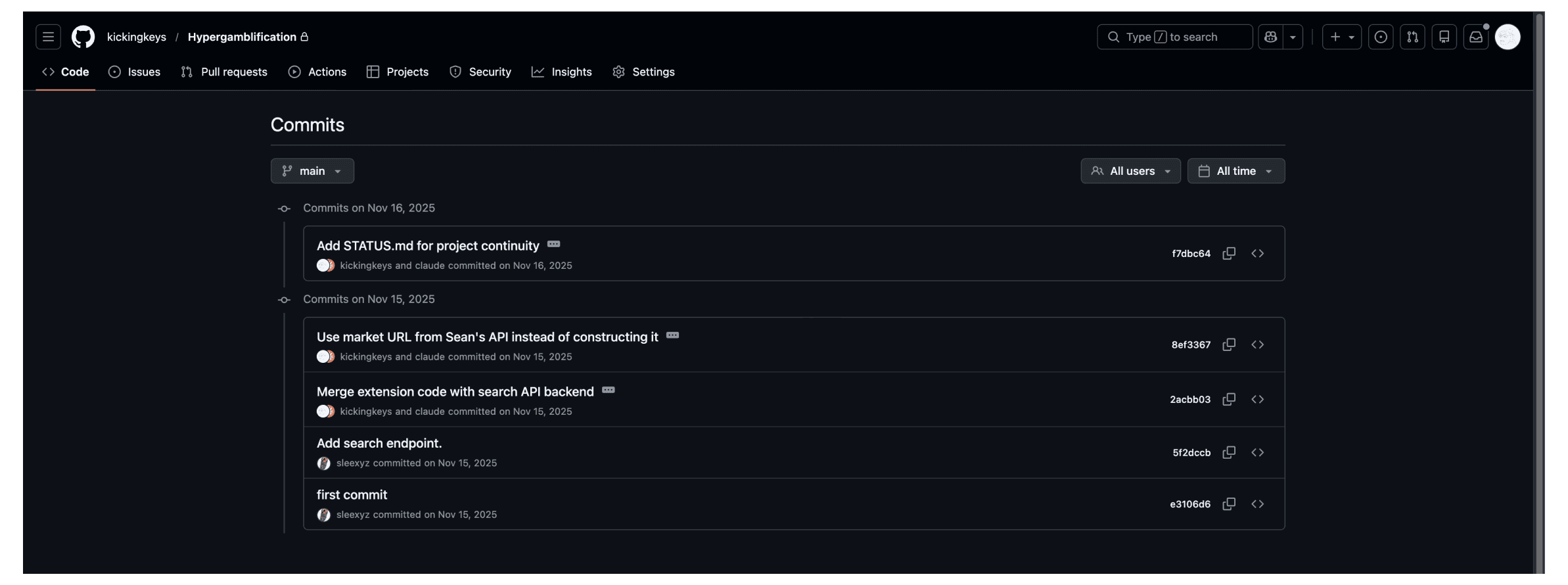

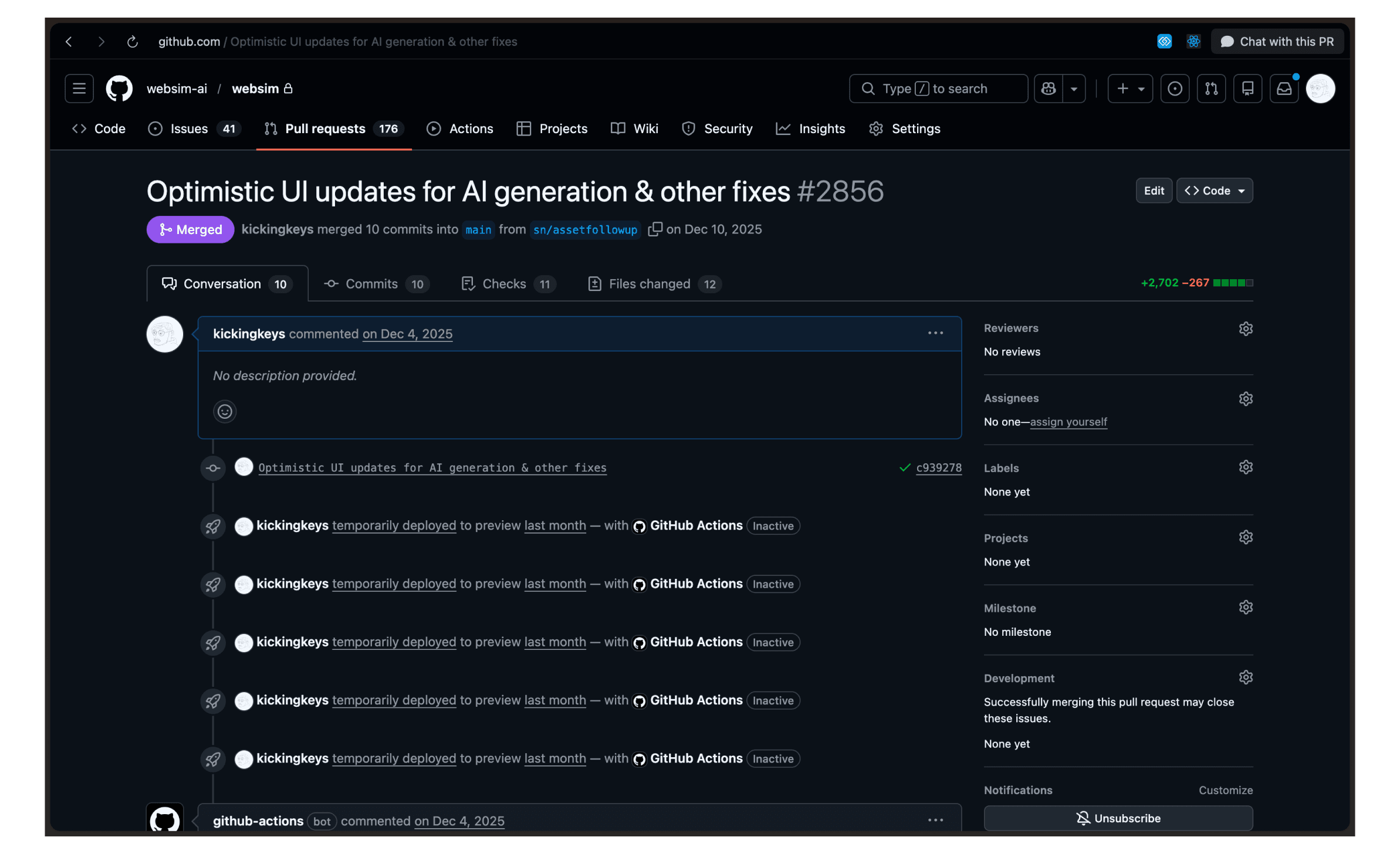

I'm a designer who started learning to write code about a year ago, most of it with AI. Now I ship production code at WebSim alongside engineers with a decade of experience. I'm not sure what to call what I'm becoming, and I suspect I'm not the only one.

On a hike in October, Max put words to what I'd been feeling: "As more people build software through AI without traditional engineering backgrounds, we'll need new languages and frameworks for that collaboration."

When AI abstracts away the syntax, more people will build software. But maybe the syntax was never really the hardest part.

What I Learned from Drafting Tables

I trained as an architect, so I've seen this before.

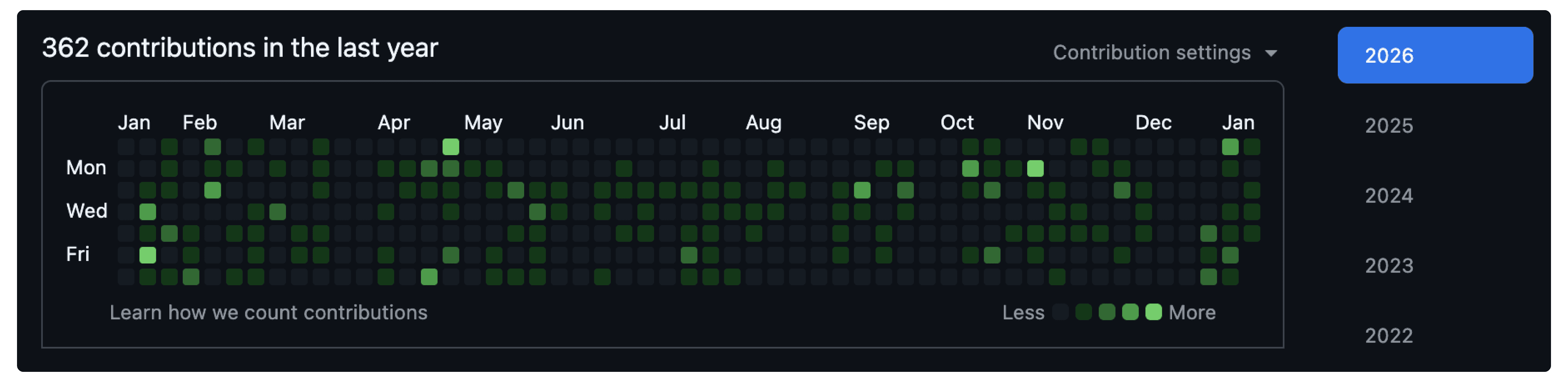

Before CAD, firms employed three draftsmen for every architect. Their job was translation: taking sketches and turning them into technical drawings. Every revision meant redrawing entire sheets. The draftsmen had construction knowledge baked into their hands. They knew what was buildable, what would fail, where the drawing was lying about what could actually stand up.

By the mid-1990s, that ratio collapsed. Architects could translate their own sketches. The bottleneck moved upstream. Firms got smaller and faster. Architects spent more time on design and less time managing the people who held the pencils.

But something else happened too. Some architects absorbed the draftsmen's knowledge along with their tools. Others just learned the software. The abstraction created room for both deeper expertise and dangerous shortcuts. You could produce drawings that looked complete without understanding what made them buildable.

Each abstraction layer kills a translation step. The work becomes about higher-order decisions. CAD eliminated drafting as a bottleneck. It did not eliminate architecture as a discipline.

And Maybe This Has Always Been True

Reading about the history of programming, I saw a similar pattern.

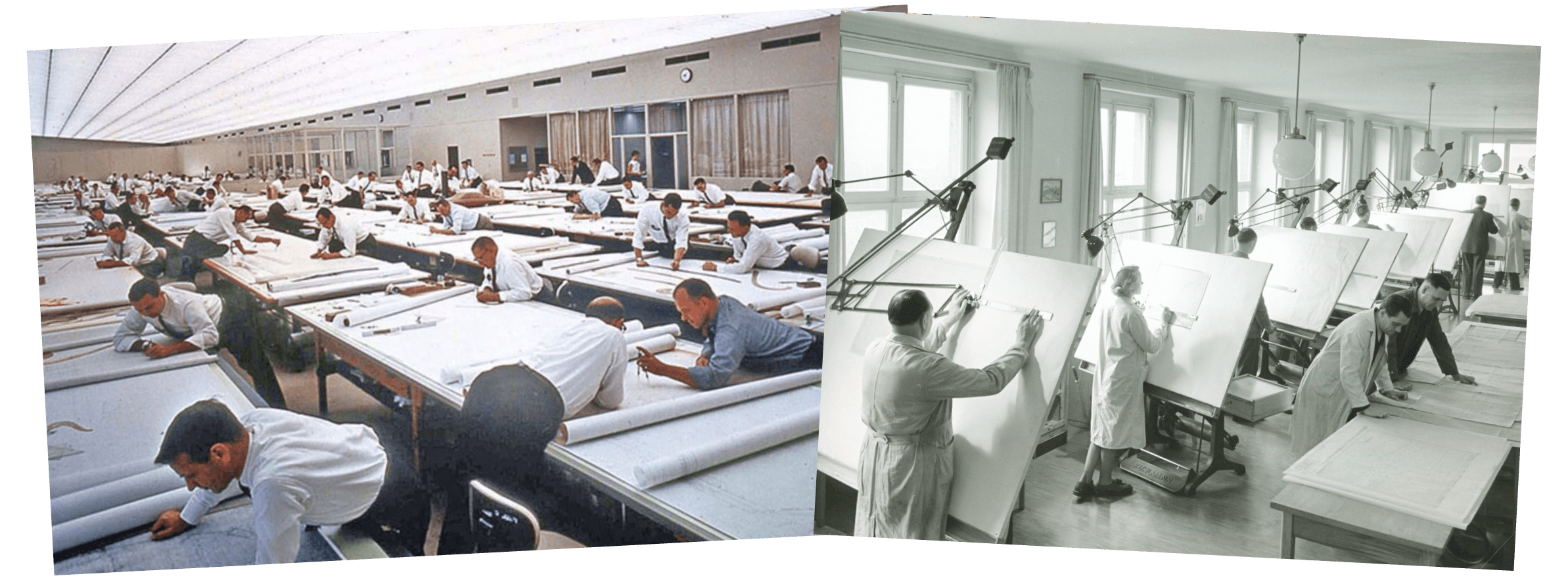

In the 1950s, programmers at IBM and Bell Labs were electrical engineers. They needed to know how transistors switched, how memory physically worked, where electrons flowed. When FORTRAN arrived in 1957, the old guard called it code for people who couldn't handle real engineering. They insisted compiled programs would never match hand-crafted machine code.

Ken Thompson, who later created Unix, estimated that 95 percent of early programmers would never have programmed without FORTRAN. The abstraction's intent wasn't making programming easier. It was making harder programming possible.

Neal, a veteran software engineer I spoke with, pointed me toward something important. The dream of making software accessible to non-engineers has existed since programming began. SQL was meant to be "English that can be executed." The abstraction has been moving away from the engineer for seventy years.

"What I sense you commenting on," he said, "is why hasn't it reached the other end of the spectrum yet? Why is there still a human engineer in the middle?"

I don't have a complete answer. But I've started to think we've been looking at the wrong bottleneck.

The assumption is that syntax is hard, so remove syntax and more people can build. But maybe syntax was never the hardest part. Fred Brooks wrote it decades ago: the hardest single part of building a software system is deciding precisely what to build. Requirements are fuzzy. Stakeholders contradict each other. The spec changes the moment someone sees the first prototype.

We've seen this pattern before. Low-code and no-code tools promised the same thing: non-engineers building software. They work beautifully for prototypes and MVPs. Then complexity arrives. Scale arrives. The system needs to talk to other systems, handle edge cases, survive the weight of real usage. The tools buckle, and engineers get called back in.

The bottleneck isn't typing code. It's making decisions under uncertainty. It's holding a system in your head while it grows beyond what any document can capture. It's knowing that this shortcut now becomes someone else's nightmare in eight months.

Pamela Zave, a computer scientist at Princeton, had an interesting perspective: the purpose of software engineering is to control complexity, not to create it. That's the job. Not writing code. Controlling entropy. And the engineer stays in the middle because someone has to own the consequences of choices, and no abstraction removes that.

What the Gap Feels Like

When engineers review my pull requests, they're not checking if it works. They're checking if it's the kind of code that will haunt us in six months.

Rob, who was a PM before co-founding WebSim, is honest about this: "For me, the bar is: does it work? For the engineers, the bar is: can we maintain this?". That gap is taste. And taste comes from experience. From writing bad code, shipping it, and living with the consequences.

Sean, who trained at Google before co-founding WebSim, put it bluntly: "Without experience, you can't have taste. Without taste, you can't make decisions. Without making decisions, you just default to what AI gives you." Your ceiling becomes whatever the model can do. And everyone else's ceiling is the same.

When someone reviews my PR and asks why I structured something a certain way, sometimes I don't have a good answer. The AI suggested it. It worked. I moved on.

The models will get better. They'll get faster, more reliable, less prone to hallucination. But that makes the danger more subtle. The output looks right. It often works. The rot is structural, invisible. You need experience to smell it, and experience is precisely what's being abstracted away.

Knowing Your Coworkers

This isn't a reason to reject the tools. I think it's a reason to develop new intuitions for working with them.

Agent orchestration is becoming its own skill. Knowing when to give a model autonomy, when to constrain it, when to scrap the context and start fresh. You start to know these models the way you know coworkers. One over-engineers everything. Another gets sloppy past a certain context length. You check work more carefully when the conversation's been going for hours, the same way you'd double-check code from a colleague running on four hours of sleep.

This is where confident ignorance becomes dangerous. Not ignorance itself. Everyone starts ignorant. The danger is confidence without feedback loops. Shipping code you can't evaluate, trusting output you can't interrogate, building on foundations you can't see.

Inside the Transition

So what do you do if you're inside the transition, building with tools that outpace your judgment?

I'm not becoming an engineer. I'm becoming something that doesn't have a name yet. I ship code by leaning on others' taste while slowly developing my own.

The apprenticeship isn't gone. It's compressed. What used to happen over years of debugging now happens in PR comments and pairing sessions. But it still requires someone on the other end who has the taste. Someone willing to tell you why your working code will cause problems you can't see yet.

I think the new languages and frameworks Max mentioned on that hike aren't just technical. They're social structures for how taste gets transmitted when the syntax barrier is gone.

The syntax layer is falling. More people will build with code than ever before. The path forward requires feedback loops tight enough that judgment can develop even when struggle has been abstracted away.

I don't know if that's possible at scale. I only know it's happening for me, one PR at a time.

References

Lohr, S. (2007). "John W. Backus, 82, Fortran Developer, Dies." The New York Times. Ken Thompson quoted on FORTRAN's impact.

Brooks, F. P. (1975). The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley.

Zave, P. & Jackson, M. (1997). "Four Dark Corners of Requirements Engineering." ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology. Zave is also cited in Esposito, D. (2008). Microsoft .NET: Architecting Applications for the Enterprise. Microsoft Press.

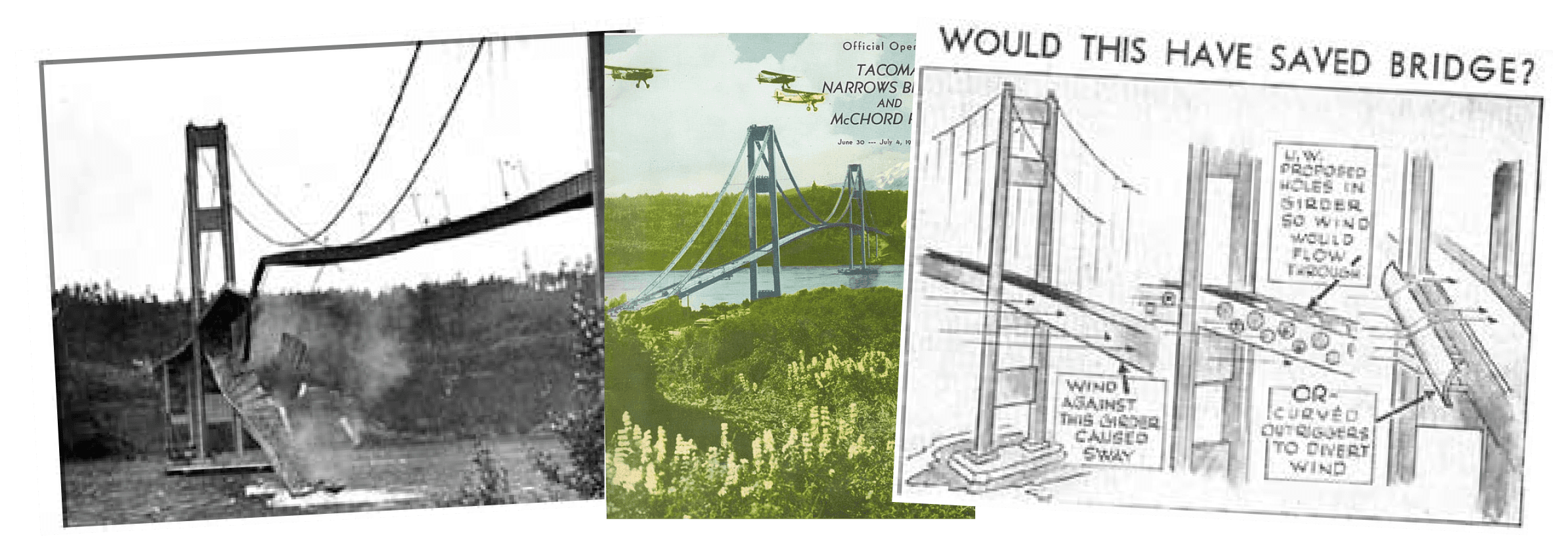

University of Washington Libraries Special Collections. Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collection. content.lib.washington.edu/farquharsonweb/

Interview with Max. (October 2025).

Interview with Rob. (October 2025).

Interview with Sean. (October 2025).

Interview with Neil. (October 2025).